The Hidden Work of Greening Richmond’s Southside: Why Autonomy Matters Beyond the Grant

by Destiny Brown, guest blogger, former Southside ReLeaf intern, and Master of Urban & Regional Planning

This feels like a full-circle moment. My first experience working with a community-based organization was with Southside ReLeaf in 2024, during a summer fellowship where I learned a great deal about what it means to do place-based, community-led work. That experience stayed with me and ultimately helped shape the focus of my graduate research while I was studying Urban and Regional Planning at VCU. Now, I get to share some of what I learned with the very organization that helped spark this research.

Where This Starts

Four volunteers work together to prepare the root ball of a tree to be planted at Boushall Middle School.

Community-based organizations (CBOs) have long been the steady, often unseen force behind efforts to revitalize, build, and protect neighborhoods. In places like Southside Richmond, this work is evident in tree plantings, community gardens, and local park revitalizations. But behind those visible efforts lies another layer of labor: applying for funding, building relationships, translating policy into action, and bearing the weight of systems that often fail to recognize or respect the leadership already present in these communities.

Urban greening requires collaborative and community-centered work, but many of the funding processes behind these projects make the work harder, not easier, for the very people who know their neighborhoods best. All the while, community leaders continue to put in the work for their communities — even as political priorities shift, funding opportunities shrink, and new restrictions make it harder for organizations to do what they’ve always done. While some changes happen at the federal level, their ripple effects are felt locally, creating new barriers to accessing support, shaping projects, and even limiting the use of DEI (or even basic demographic) language in grant proposals and applications.

The tension between visible community work and the hidden obstacles that accompany it led me to explore these dynamics more deeply through my master's thesis research. What follows here is not just academic; it's personal and inquisitive, rooted in Richmond, and shaped by the work happening right here in Southside.

What I Found

To provide a transparent account of my research, these are the guiding research questions:

How do funding criteria and government policies influence CBOs' strategies to advocate for greening projects?

How do power imbalances between CBOs and funding entities shape decision-making in urban greening initiatives?

How do CBOs build partnerships with government agencies or funders to influence greening policies, and why are some partnerships more successful than others?

After 10 months of reading, highlighting, and taking notes in the margins of documents, as well as searching archives for documents and websites that are no longer accessible, I found the following:

Grants Reduce Autonomy: The money exists, but it may come with strings that require CBOs to adjust their projects to someone else's vision.

Visibility Doesn't Equal Power: CBOs are frequently highlighted in press releases and media posts, but that visibility doesn’t equal influence over decisions and policy.

The Limitations of Community Participation: While funders may celebrate "community involvement," the actual power to shape projects is generally not held by a community stakeholder.

Structural Barriers Reinforce Old Patterns: Although grants may be available, they're not always accessible, particularly for smaller groups lacking the administrative resources to meet technical requirements.

Still, CBOs persist. Not because the systems are easy to work with, but because the work matters that much. The work has to be done, and as always, the community will find a way to, at the very least, stay afloat while turmoil surrounds and neglect prevails.

What Would it Look Like if Things Were Different?

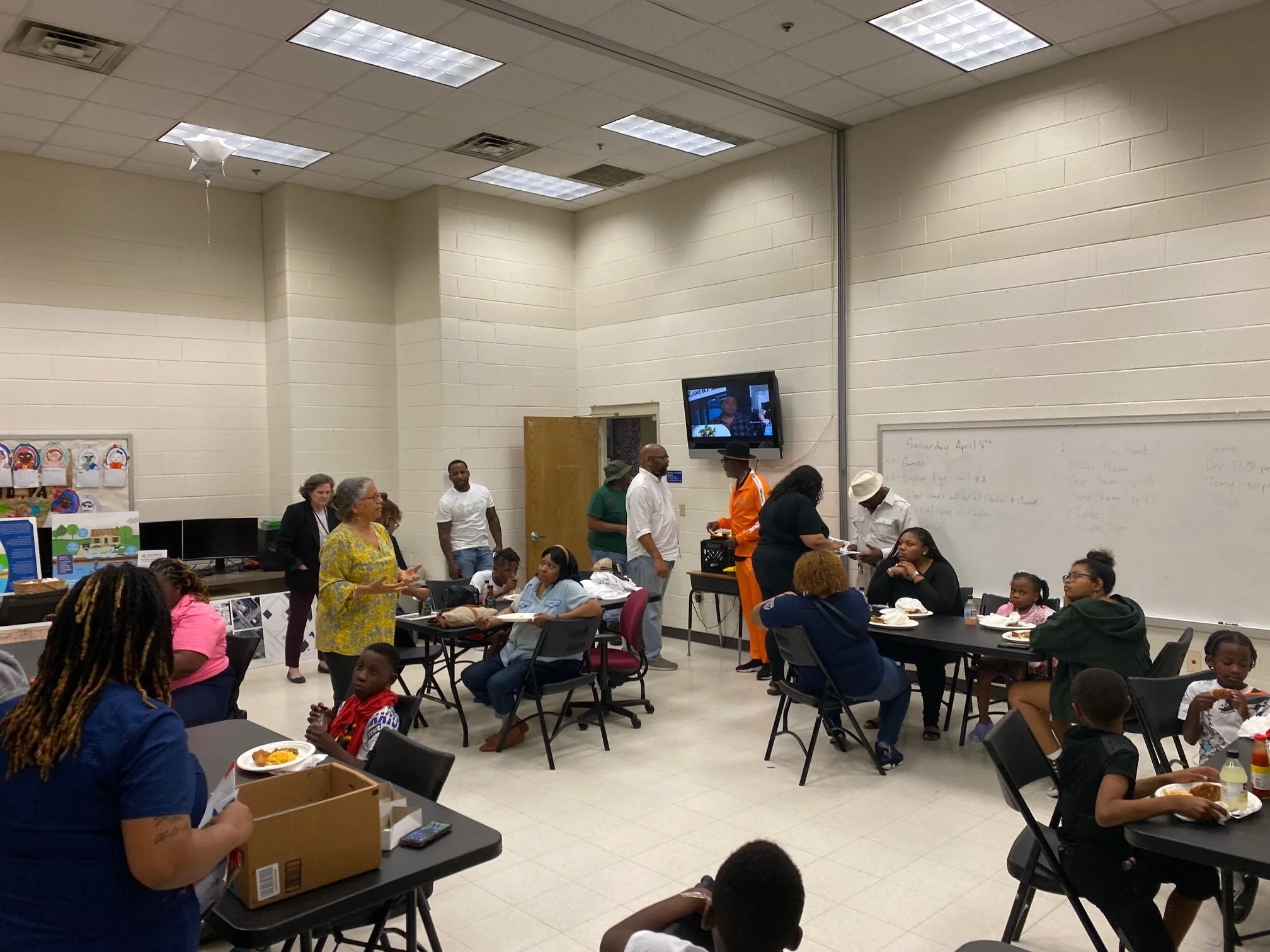

Community members gather at Blackwell Community Center in April 2023 to provide feedback on the green upgrades they want at Blackwell Park.

What if we started from a place of trust? What if funding prioritized repairing past harm and restoring relationships, not just supporting projects that check boxes for funders but don’t always reflect what the community needs to heal from historical and systemic injustices?

Greening efforts should be rooted in:

Funding through a reparative justice lens — one that repairs harm with intention, rather than simply rewarding organizations that happen to align with traditional funding expectations.

Greater autonomy for CBOs (if they want it), with the flexibility to shape projects in ways that reflect local priorities.

Power mapping tools to help organizations see clearly where influence sits and how it might shift.

Community impact assessments that look beyond planting numbers to ask: Did this project improve the daily lives of residents? Did it build long-term power in the neighborhood?

It's not about rejecting help or collaboration from the government or external support, but rather about shaping processes that begin with community leadership, not just including it as an afterthought. This approach is similar to collaborative governance, where decisions are shared, not just informed.

If you’re curious about understanding what a reparative justice approach to funding looks like, read the Literature Review and Recommendations in my thesis for greater analysis.

Why This Matters

A large group of volunteers wearing safety vests pose with the pile of tires and bags of trash they cleaned up along Ernest Road during a service day to honor Martin Luther King Jr.

Southside Richmond has come a long way from the harm caused by systematic and intentional decisions, such as redlining, urban renewal, highway expansion, housing displacement, and annexation — decisions shaped by longstanding power imbalances. But the work is far from over. The vision continues to grow, and the story doesn’t belong to one person or organization; a whole community of storytellers carries it.

This work can't be about pride or who gets to claim they "made the change." The community itself should have the opportunity to recognize and define what changes are needed and what progress looks like. While policies shift, initiatives lose funding, administrations change, and government priorities fade away, the people remain. The residents, the organizers, the advocates, the CBOs — they stay rooted in their "why." Not because it's profitable, but because it's personal. For many, it's not really a choice.

I don't claim to have all the answers. But what I do know is this: the people doing the work — the CBOs, the neighbors, the residents — are showing up every day. Maybe that's who should have more power. More voices. More control. Perhaps the most radical thing we can do is envision a system where that work isn't constantly hindered by outdated systems and questionable traditions, but instead supported, trusted, and resourced as it deserves to be. We've seen radical visions come to life before. It can happen again.

Read Destiny Brown’s thesis for her Master of Urban and Regional Planning Capstone: Exploring the Role of Government Funding and Policy Criteria in Greening Projects: A Case Study of Southside Richmond.